You’re receiving this message because your web browser

is no longer supported

We recommend upgrading your browser—simply click the button below and follow the instructions that will appear. Updating will allow you to accept Terms and Conditions, make online payments, read our itineraries, and view Dates and Prices.

To get the best experience on our website, please consider using:

- Chrome

- Microsoft Edge

- Firefox

- Safari (for Mac or iPad Devices)

el salvador

Get the Details On Our El Salvador Adventure

Find out more about the adventure, including activity level, pricing, traveler excellence rating, included meals, and more

Spend 2 days in El Salvador on

Route of the Maya

O.A.T. Adventure by Land

Adventure Details

Add Adventure

including international airfare

per day

*You must reserve the main trip to participate on this extension.

**This information is not currently available for this trip. Please check back soon.

You may compare up to Adventures at a time.

Would you like to compare your current selected trips?

Yes, View Adventure ComparisonEl Salvador: Month-By-Month

There are pros and cons to visiting a destination during any time of the year. Find out what you can expect during your ideal travel time, from weather and climate, to holidays, festivals, and more.

El Salvador in November-January

Out of El Salvador's two seasons, the dry season in November through April is the better time of year to visit the region. December is considered the best time to travel to El Salvador when the weather is comfortable and the air is fresh.

These summer months are ideal for experiencing San Salvador's bustling city and hiking through Cinquera National Park's tropical landscape. During the summer, expect larger crowds of tourists flocking to the region to experience the warm and pleasant weather, as well as the holiday season in December.

Holidays & Events

- November 1: All Saints' Day commemorates every Christian saint.

- Late November: Carnival de San Miguel honors the patron Our Lady of Peace and is marked by processions, dancing, and musical performances.

- December 25: Christmas Day is a time for family members to come together in one place and celebrate the holiday together. The night before, on Christmas Eve, the whole family gathers together for a meal followed by a fireworks display.

El Salvador in February-April

The dry season continues through April. Temperatures average around 80-90 degrees Fahrenheit, with the hottest of the summer weather occurring in March and April. Similar to November through January, you can expect larger crowds of tourists in the region who are looking to experience the warm weather, as well as Holy Week in March.

During the warmer months, you will have the best opportunities to view wildlife—perhaps you'll spot monkeys, snakes, and parrots as you explore Cinquera.

Holidays & Events

- Weekends in February: The International Festival of Art and Culture in Suchitoto is a celebration of international art. Artists from around the world showcase their displays, music, dances, and films.

- March 17:The Feast of San Jose is celebrated in northern El Salvador in Agua Caliente. Typically, locals taking part in the day's festivities attend celebratory rodeos and processions.

- Late March: Semana Santa, or Holy Week is the week leading up to Easter.

- Late March or early April: Easter Sunday concludes Holy Week. Vigils are held Saturday night through Easter Sunday.

Must See

If you're traveling to El Salvador in February, The International Festival of Art and Culture is an annual event that brings together artists from around 30 countries who travel to Suchitoto to display their talents. The event includes work from musicians, actors, dancers, and filmmakers. And, if you're in El Salvador in March, you'll experience Semana Santa, or Holy Week. Processions are the main events of the week leading up to Easter, but locals also have the chance to show their creativity. Locals cover the streets in vibrantly colored sand that is arranged to portray biblical scenes and elaborate designs.

El Salvador in May-October

May through October are considered El Salvador's winter months. El Salvador doesn't experience a traditional winter—temperatures remain warm with average highs in the 80s in cities like San Salvador. Be sure to pack lightweight clothes and rain gear because winter is also the country's rainy season. June through September see the most rainfall over the winter and storms are common this time of year. Fortunately, the tropical region is only affected by moderate storms and doesn't typically get hit by hurricanes. If a little rain doesn't bother you, this is a great time to travel to El Salvador when fewer tourists are exploring the region. You'll avoid the crowds and see important sites uninterrupted like Joya de Cerén—an archaeological treasure chest—and Suchitoto—a quaint colonial town.

Holidays & Events

- Throughout July: The Julias Festival is celebrated in Santa Ana.

- First weekend in May: The Festival of Flowers and Palms honors the Virgin Mary and is celebrated with processions, dances, and preparations of a variety of traditional cuisines.

Must See

The month-long Julias Festival honors Saint Santa Ana and runs through the end of July. Locals fill Santa Ana's colonial-style streets where they enjoy a variety of musical performances, carnivals, and parades. One notable parade is the equestrian parade, which brings together hundreds of riders and their horses.

El Salvador in August-October

The rainy season continues through October. If the wet weather doesn’t bother you, August and September might be ideal times to visit. These months see the most rainfall with averages totaling up to 11-14 inches. The excessive amount of rainfall means fewer tourists and more uninterrupted discoveries. In addition to rain, the winter months typically see storms, but fortunately, El Salvador rarely gets hurricanes. Similar to May through July, it’s advisable to pack lighter clothes to keep you cool and water resistant outerwear to keep you dry from the rain.

Holidays & Events

- First week in August: The Festival of El Salvador is dedicated to "the Savior of the World."

- August 31: Las Bolas de Fuego is a fiery festival that is held yearly in Nejapa, a small town located around 30 minutes outside of San Salvador.

Must See

The Festival of El Salvador is an annual celebration of the Divino Salvador del Mundo, or Savior of the World. The main festivities take place in San Salvador where thousands of locals fill the streets to take part in processions, watch colorful parades, and enjoy traditional music. But, a statue of Jesus being carried around the crowded streets is considered the main event.

If you're interested in a more thrilling event, the Bolas de Fuego festival is held on August 31 and commemorates a devastating volcanic eruption that shook the tiny city of Nejapa in 1922. Locals split into teams and each team member douses rags in kerosene. The rags are then set on fire and members throw the rags at opposing team members. The tradition has been celebrated for decades and is meant to represent the eruption that destroyed the town years ago.

Average Monthly Temperatures

High Temp Low Temp

El Salvador Interactive Map

Click on map markers below to view information about top El Salvador experiences

Click here to zoom in and out of this map

*Destinations shown on this map are approximations of exact locations

San Salvador

A year after the Spaniards entered El Salvador in the early 16th century, San Salvador was established as the center of Spanish conquest in Central America by Pedro de Alvarado, a Spanish conquistador—Spanish for “conqueror”. Even after the region won its independence in 1821, San Salvador served as the united Provinces of Central America’s capital. When El Salvador eventually gained complete independence in 1841, San Salvador remained the capital of the country. El Salvador's largest city has a deep respect for its history and cultural heritage, which is evident at the Museo de la Palabras y la Imagen, or the Museum of Word and Image, which houses an impressive collection of historic artifacts and photos.

The Catedral Metropolitana de San Salvador was visited twice by Pope John Paul II, who said the building was “intimately allied with the joys and hopes of the Salvadorean people.” The main altar features an image of the Divine Savior donated by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in 1546, and features a churrigueresque, an ornamental sculpture prominent in 18th-century Spanish cathedral construction. The famed Archbishop Óscar Romero is entombed in the cathedral after his assassination in 1980.

Today, more than half a million residents live in this cosmopolitan hub, which is just in reach of mountainous wonders and stunning beaches. The capital also sits on the Cocos tectonic plate whose movement has led to devastating earthquakes in recent years. In the background of San Salvador’s cityscape looms the city’s famous volcano. Fortunately, the San Salvador Volcano hasn’t erupted since the early 20th century. At the tip of this volcano is El Boquerón National Park. This national park, whose name means "big mouth," boasts breathtaking views of the crater and beyond, and has several hiking trails along the volcano that will give you a glimpse of the area's distinct flora and fauna.

Explore San Salvador with O.A.T. on:

Joya de Cerén

Despite being buried in the sixth century by a volcanic eruption, Joya de Cerén is an archaeological dream due to its highly preserved condition and abundance of artifacts that provide a glimpse into the lives of the inhabitants of this ancient city. Known as the Pompeii of El Salvador, Joya de Ceren is an ancient, pre-Hispanic, 7900-acre village that is frozen in time. While no human remains were found at the site, evidence of pots, garden tools, and animal bones is present. Archaeologists believe that the village's residents were able to escape before the dangers of the eruption reached the area. While most Mesoamerican ruins have traces of temples or royal artifacts, Joya de Cerén was most likely a farming community. Uncovered in 1976, the ruins were designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993.

Explore Joya de Cerén with O.A.T. on:

Suchitoto

Suchitoto, meaning "bird-flower" and charmingly nicknamed "Suchi," is a quiet colonial town that was established by the Pipil people (descendants of the Aztecs) around 1,000 years ago before being conquered by the Spaniards, who established the capital near the town's current location. Today, Suchitoto is known for its creative spirit, in part thanks to local filmmaker Alejandro Coto who preserved the history and culture of Suchitoto and El Salvador in his films. The filmmaker was so important and respected in the country, that his home in Suchitoto was converted into a museum dedicated to his life and work. This creativity is also celebrated at the town's many arts festivals that take place regularly throughout the year.

The tradition of filmmaking lives on in the city’s almost weekly arts events and the Permanent International Festival of Art and Culture throughout February, where representatives from over 30 countries attend annually. Another major celebration is the Parade of Torches and Costumes in September, where the streets fill with music, dance, and people in costumes representing the many legends and traditions of Suchitoto.

Outside of the city's colonial architecture and prominent 19th-century Santa Lucia Church, Suchitoto has an abundance of natural wonders. Stroll around Lago Suchitlán to take in views of the expansive lake and the surrounding verdant hills—you may even spot a hawk or falcon flying overhead as Suchitoto is home to more than 200 bird species.

Explore Suchitoto with O.A.T. on:

Cihuatán

Moss-covered temples and ball courts mark the ancient ruins of Cihuatán. This site is believed to have been established around AD 900 and was inhabited by the Maya and Lenca who enjoyed a short period of prosperity before the ancient city was destroyed in the tenth century. Archaeologists believe that a fire swept through the city during the warmer, dry months, causing the residents of Cihuatán to abandon their homes and belongings. Today, Cihuatán is El Salvador's largest archaeological area.

Explore Cihuatán with O.A.T. on:

Cinquera

Travel off the beaten path to get a glimpse of the turbulent history and natural beauty of Cinquera, a small, mountainous town with a population of around 1000 people.

In the late 20th century during El Salvador's Civil War, Cinquera was the target of violent attacks by the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), a rebel group disguised as a political party in El Salvador. Today, the central El Salvadorian town rebuilds itself, but permanent scars from this dark period in time still lingers. Bomb- and bullet-damaged buildings line the streets, and the town even established a Museum of Historical Memory to remind locals of this complicated part of Cinquera’s past and to ensure that history doesn’t repeat itself. Out of the darkness, Cinquera has become a model for locally-led, sustainable development with an emphasis on youth, historical memory, and environmental preservation.

Despite Cinquera’s violent history, there’s still beauty to be found here in Parque Ecológio. This 9689-acre park is a serene getaway from the city as it boasts small waterfalls, a lush rain forest, and scenic hiking trails.

Explore Cinquera with O.A.T. on:

Ruta de las Flores

Along the Ruta de las Flores, or Flower Route, is an intermingling of spectacular natural wonders and insightful cultural attractions. Discover the route's verdant setting, where waterfalls rush down craggy mountains and volcanoes dot the landscape. The nutrient-rich soil that surrounds the volcanoes is ideal for cultivating coffee plants, an important crop to El Salvador. After the stock market crashed, Nahuatl coffee farmers were hit hard in 1932. The coffee farmers grew poorer and the landowners grew richer, causing tension between the two classes. As a result, the farmers revolted against the wealthy elite, but the government took action to suppress this group by killing nearly 30,000 locals in what became known as the Peasant Massacre.

In terms of coffee, the small mountain town of Ataco is world-renowned for having the best coffee in Central America. With some of the best land for growing the crop, Ataco has developed an economy based on coffee with many coffee shops and retail stores to bring it to the masses.

Today, the 22-mile Ruta de las Flores takes travelers to the heart of Salvadorian culture and history where food and craft festivals abound. Visit towns like Juayúa and Sonsonate to get a true glimpse of life along the route. Juayúa, one of the town's where the Peasant Massacre occurred, is known for its picturesque, cobbled streets, nearby natural wonders, and a 16th-century Black Christ statue, while Sonsonate is a quiet town located at the end of Ruta de las Flores that is known for its colonial-style architecture.

Explore Ruta de las Flores with O.A.T. on:

Featured Reading

Immerse yourself in El Salvador with this selection of articles, recipes, and more

ARTICLE

The Mayan empire fell centuries ago, but their legacy is still felt throughout Central America.

ARTICLE

The ancient group painted human sacrifices head to toe in “Mayan blue.” Discover more about the Mayans.

From Ancient Empire to Contemporary Culture

The Maya then and now

for O.A.T.

Although the Mayan Empire ended, the Maya continued to thrive in agricultural villages throughout the mountains of Central America ...

When Hammurabi ruled Babylonia and the ancient Egyptians were under Hyksos influence in the 13th Dynasty, another great empire was forming in the Americas. The ancient Maya began as farmers but went on to develop some of the most advanced forms of architecture, mathematics, language, and religion known to the Americas at the time. Even after the end of their 2,700-year reign of power in the region, the Maya continue to wield their influence on contemporary Central American culture, particularly in Guatemala, where modern Maya people comprise approximately 40% of the population.

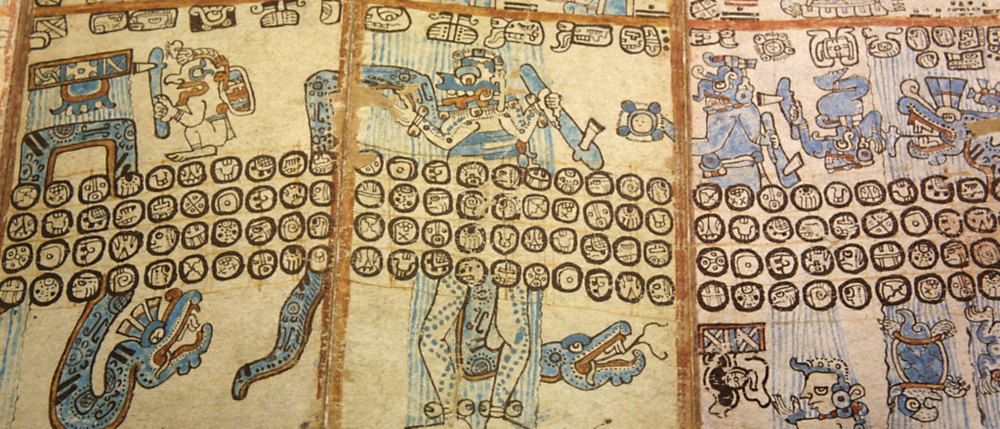

Using glyphs to understand the past

It is through ancient Maya monuments, art, and architecture that scholars learned about the system of Maya writing, which many suspect is ancient Mesoamerica’s first writing system and the only ancient language in this region to be comprehensively translated. One of the landmark examples of Maya writing is the Hieroglyphic Stairway, consisting of 1,800 ascending glyphs in Copán, an ancient Maya city in western Honduras. While ancient Maya scribes created glyphs both in stones and in paper texts, the Spanish conquistadors burned most of the paper texts in the 16th century while converting the Maya to Christianity, and discouraged the use of Maya script. After the last of the Maya scribes died out, the text remained untranslated until Western explorers in the 1880s renewed interest in the glyphs.

The glyphs themselves were not fully translated until the 1980s—and a world of dynastic succession and a society beset with violent conquest and gruesome religious sacrifice came to life. The texts and stone carvings also illustrate vivid mythologies, the most seminal of which involves mortal twin brothers fighting gods in the underworld, eventually going on to feed the Maya and then transforming into the sun and moon.

Uncovering the world of everyday Maya

While ancient cities like Copán and Tikal harken to a golden age of architecture, art, and ideology in Maya civilization, our understanding of ancient Maya life greatly improved with the 1976 discovery of the village of Cerén, located in western El Salvador. Called “the Pompeii of the New World” because it was enveloped in volcanic ash in AD 590, the site serves as a time capsule for daily life in a small village of that era. Though it appears the residents had time to escape the eruption, they left behind an impeccably preserved village. Excavations revealed that cassava was widely grown. Some archaeologists have posited that this hardy, nutritious tuber—which remains a staple to this day—may have enabled the Maya Empire to accommodate up to two million subjects at its peak.

Although the Maya Empire ended, the Maya continued to thrive in agricultural villages throughout the mountains of Central America—and their cultural heritage still lives on today. Throughout Spanish conquest, they maintained the spoken language of their ancestors, of which there are dozens of dialects spoken in Guatemala alone. Maximón, the ancient Maya god of the underworld, was reincarnated as San Simón after hundreds of years of forced conversion of the Maya people to Roman Catholicism. In addition to a name change, Maximón also got a bespoke makeover and is usually seen in 18th-century European clothes. Many handcrafts produced in the region today reflect the art of their ancient ancestors, such as jade carvings and intricate textiles. The historic and contemporary legacy of the Maya serves as a window to their civilization at its peak, a haunting reminder of the impermanence of great empires, and a reminder of how the roots of the past give shape to a vibrant modern existence.

The Maya then and now

7 Things You Never Knew About the Maya

Shedding light on an ancient empire

by David Valdes Greenwood, for O.A.T.

Between 250 and 900 AD, the Maya reigned in Central America. But by 1000 AD, they had vanished—taking many of the keys of their culture with them.

Still, some fascinating facts have been gathered, and below, you can test your knowledge of this once-thriving civilization:

1. They had their own Farmer’s Almanac

You probably knew the Maya created a written language (the only one in Mesoamerica), but did you know they wrote books, too? These codices—one of which was 122 pages long—included predictions for the tides, eclipses, weather patterns, and sun cycles. Sadly, when the Spanish conquistadors arrived, they burned all but four of these books.

2. They were never satisfied with their looks

From an early age, the Maya tried to change their features: They hung little balls close to babies’ faces to make them cross-eyed, attempted to flatten their children’s foreheads by strapping boards upon them, and modified adult teeth to keep up with local beauty notions—adding inset gems and precious stones for personal style.

3. The Mayan underworld was literally under foot

The underworld was known as Xibalba, and it could be entered easily: A massive waterway flowed beneath Mayan territory, with 2,500 natural entrances (known as cenotes) leading to subterranean cave networks. The Maya believed they could feel the pull of the underworld by standing in a cenote–which explains why it was a site for human sacrifices.

4. They lost their minds over sports

At Copán and elsewhere, they built massive courts for a game similar to racquetball—only the ball they used was much heavier. And depictions of the game are disturbing: Decapitation is a common element, leaving experts unsure if the hefty ball could knock the players’ heads off, or whether actual skulls were used in game play.

5. “Mayan Blue” was a color to die for

The Maya created a blue pigment that was almost indestructible—in fact, it’s still visible in pottery and murals more than 1,500 years later. But some uses of the color were intended to be literally perishable: at Chichen Itza, human sacrifices were painted Mayan Blue head to toe before being offered to the gods.

6. Pregnancy earned women spa days

The Maya loved spending time in a zumpul-ché, a vented stone chamber where water was poured over hot rocks, yielding steam to bask in. Similar to a modern sauna and used for restorative purposes, they were popular with expectant mothers in need of a boost.

7. Some cherished traditions live on

In Hetzmek, the ancient Maya version of a christening, a child of three or four months was carried on a godparent’s hip, the infant’s legs straddling either side. The open legs symbolized the community preparing the child to walk through life. Hetzmek was being practiced when the Spanish arrived, and the tradition is still observed by many of the seven million Maya who still live in the region today.

Shedding light on an ancient empire

Traveler Photos & Videos

View photos and videos submitted by fellow travelers from our El Salvador adventures. Share your own travel photos »